What started off at the home of my good friends, mentors, and agents home in Chapel Hill, NC has now come into reality. I am off to the Pacific Northwest to pursue a journey that has taken ten years to arrive at. A journey that has played out in the spirit of the stop-motion process. Honored to have entered this next stage of creative development and application. Thanks Weinraub + Kass for believing in a man and helping to scale the order of his talents.

DEC. 09, 2020 Tory Bryant

OCT. 22, 2020: Adventures in Rapid 3D Resin Printing Part 01: Start Early to be on Time

Starting early to be on time

This great animated shot progression of Sir Lionel Frost, by Sunny Wai Yan Chan allowed me to study the subtleties needed to breakdown the components that I used in developing my visual reference guide.

JUL. 20, 2020: 15 Years Ago Today...

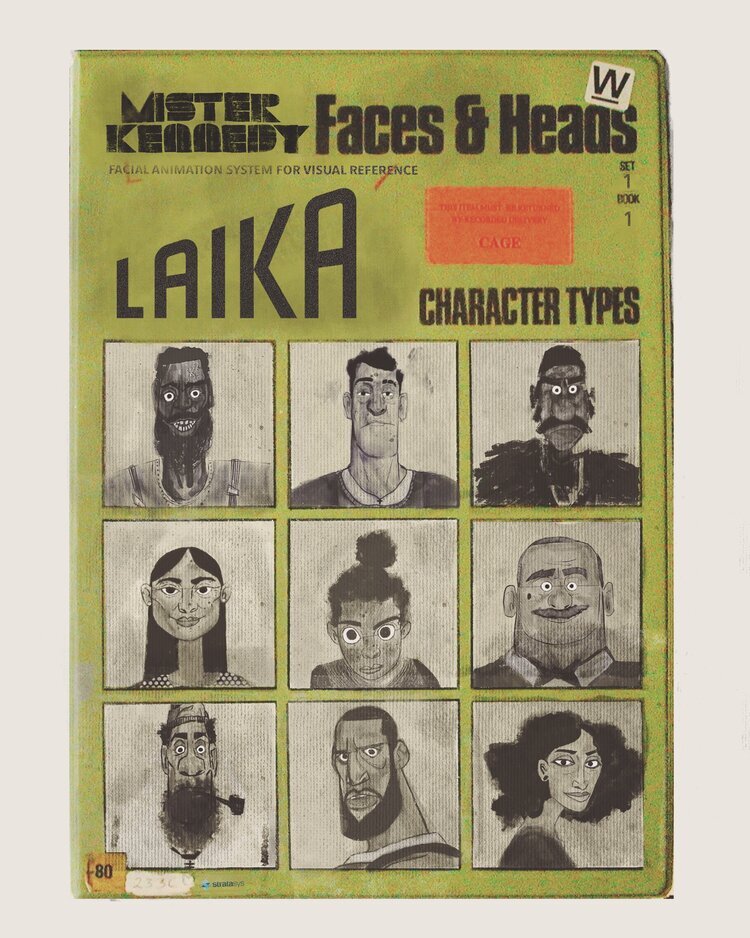

MAR. 08, 2020: Facial Animation System For Visual Reference

In the coming months, as time permits I’ll be putting together a facial expression reference guide to aide in analyzing the performance of some of my characters. Trying to find ways to move beyond the basics of motion and timing, into proper timing that establishes the ideas behind the actions as well as the audience’s interpretation of it.

Been paging through the art of books, asking friends to act out lines, getting advice from fellow animators, and toggling frame by frame through my film library in order to craft face moves according to realistic musculature; with hyper-accurate lipsyncing and anatomical accuracy, regardless of how stylized the character might be.

Should be able to share some results with folks later this year.

FEB. 01, 2020: Making of Missing Link...

JAN. 24, 2020: Behind the Science of LAIKA: Animating Faces

JAN. 22, 2020: Credited As: Head of Puppetry

Georgina Hayns, takes viewers behind the scenes to show what she does as the head of puppetry.

JAN. 20, 2020: THE ART AND SCIENCE OF LAIKA

AT&T Developer Program: The Art and Science of Laika

Go behind the curtain with Brian McLean and Steve Emerson of LAIKA, the stop-motion animation studio that connects the new with the timeless to tell enduring stories by fusing filmmaking's state-of-the-art technologies with a handmade animation tradition as old as film itself.

DEC. 31, 2019: Entering Into a New Chapter. There’s Levels to This, Levels…

NOV. 09, 2019: The Story So Far...

There has been a steady stream of Making of’s rolling out with the Award session kicking off. One of the things outside of great storytelling that brought me to LAIKA is the behind the scenes shorts on how the studio is a band of artists and technicians working together to craft the best animation in the industry.

I knew after seeing the In Their Hands marketing short that LAIKA was the only studio that I wanted to contribute my talents towards. There’s an artist magic that is projected into each feature, that allows for inspiring family entertainment that has become scarce throughout the decades, while Pushing the medium forward in terms of artistry and narrative. Below is a recap of how the shorts add immediate value to the process that we all strive to execute each time we step into the studio.

I’ve begun pooling my years of notes, research, and experiences into an academic reader, as I'm structuring for my thesis. With this being said I have some more great news to announce in the coming months.

OCT. 26 2019: Screening Series |Missing Link Q&A at the Landmark

AUG. 18, 2019: STOPS: Dynamics for LAIKA Films | Peter Stuart & David Horsley | SIGGRAPH 2019

Laika's preferred dynamics isn't really a heck of a lot different from any other studio but we do stylize our work to meet established criteria for our show style, and we do need to be able to integrate our work with the stop motion animation. In short the work needs to look, animate, and feel realistic yet convey a sense that it was created on our stop motion stages using practical materials like paper or cloth.

Peter Stuart has been a Senior Generalist TD at LAIKA since 2006 to present. He was a Shader Writer for the Core Feature Animation team before that and has worked on Missing Link, Kubo and the Two Strings, The Boxtrolls, Paranorman, Coraline, and The Wild. He received a MS Computer & Information Science from Ohio State University and a Physics BA from the University of Montana.

David Horsley was hired at Laikato work on “Kubo and The Two Strings” as a Lead to help the VFX department complete all the water shots for the film. His work on The Life of Pi and VES award for the work on that film secured him the job in 2014. Since then he has completed “Missing Link” which also involved considerable water work.

His career as an FX Supervisor incorporates twenty years of innovative, visual effects experience on feature films, using Houdini software for lighting, visual effects, look development, and bidding on new projects. His technical experience specializing in water, snow, ice, metal, fire and fluid effects, enhances his abilities to work well under pressure, visualize the demands needed to support production, client, and artistic challenges.

MAY. 24, 2019: The ROBOTS of LAIKA: Implementing New Technology in a Creative Environment with Steve Switaj

MAY. 04, 2019: 'Missing Link's Costume Designer Deborah Cook Has The Job You Never Knew Existed...

Here’s a great read that I discovered the other day from Ani Bundel of Elitedaily.com on LAIKA’s talented Costume Designer Doborah Cook and their current masterwork Missing Link. Enjoy!

Nearly everyone knows LAIKA Studio's stop-motion animation work. From the adaptation of Neil Gaiman's Coraline to the adorable The Boxtrolls, the studio has been nominated for six Academy Awards. The latest release, Missing Link, is another visually stunning achievement. It's also a period piece. But fans might not realize creating the Victorian-era looks for the puppets is a real job. Missing Link's costume designer Deborah Cook didn't start out planning to dress tiny characters for the big screen.

Cook explained the path that brought her to stop-motion wasn't the most straight-forward. Her original intent was to become a sculpture artist. "Before I did sculpture, I would collect fabrics and textures and items and make them into three-dimensional shapes, even as a small child," she explains to Elite Daily.

"I studied fine arts sculpture and did a postgraduate in sculpture. My work was really about creating environments and installation work. I would do costume pieces alongside abstract furniture, pieces on the wall, and film them, moving them around."

Her installations were what caught the attention of those in the stop-motion animation field. "A lot of stop-motion studios started to approach me to help on their projects. I loved how you can almost put more detail in a smaller piece than a bigger one when you project them so large. Some of those characters are nine to 14 inches tall. You can get a whole lot of detail into those costumes."

Cook has built costumes for every LAIKA production thus far. With Missing Link, her designs were all based in the late Victorian/early Edwardian era. Describing the precise attention to detail, she says, "One of the things we wanted to do with the costumes was traditional Victorian tailoring but bring something new and more lively. The era, 1890 to 1910, was the cusp of synthetic dyes coming into play so we could use fuchsia pink for Adelina's dress or turquoise for Lionel's cravat and those really punchy colors."

In Missing Link, the title character, Link, towers at 16 inches tall. His costumes, which are human clothing, stick out both for their color scheme and their bad fit.

"In the story, [Link's] suit is stolen from someone in the bar brawl, and [he's] wedged himself into it. The colors, the pattern, that bar, and that area being the pacific northwest of America, the history of that area was loggers who would have worn woven clothing, which was made by only a couple of very instrumental companies... The plaid comes from that."

Cook says for some if the costume accessories, like gloves, the production gets remnants and scraps from factories that make real sized ones. But in most cases, materials aren't sold in stores.

"We don’t buy off the shelf anymore. We’ve become more self-sufficient. That way we can embed the needs of the animation into the fabric, so we can weave in wires for example, or make sure there’s a certain stiffness in certain areas in the backings that we need. We make lots of backups. They get handled more than they might if they were just a regular costume by several different animators, or by maintenance people."

So how does one land a job in the field of stop-motion animation? Cook says most stumble across it much as she did. "A lot of people don’t come directly from animation schools. We have set dressers, costume fabricators, silicone model makers, and carpenters, all kinds of people working on the set."

Her advice to anyone who wants to get started: "Just follow what you love doing, make the most of your environment, and make the most of everything you can learn."

Missing Link is out in theaters now.

Also take a look at Deborah explaining the process of costume designing from the Academy Originals Creative Spark Featurette.

APR. 14, 2019: Dedicated to Fusing Art and Technology | Evolution of Rapid Prototype at LAIKA

Took my family to see Missing Link for my daughters birthday and I have to say the team of artists and scientist up in Hillsboro never fail to create movie magic and continue to motivate me on my goals of working at the studio this year. Invention, innovation and adaptation are said to all be creative processes that that apply exiting solution, techniques or products to new scenarios or changed conditions. Innovative creativity however, refers to thinking that results in new solutions and the ability to do things differently than they’ve ever been done before.

These thinkers and artists often challenge our existing paradigms to uncover and question the status quo. This might be the category of creativity that drives Brian McLean, Head of Rapid Prototyping at LAIKA to think differently about the ways to make an animated film, incorporating 3D printing technologies to bring their ideas to life.

Here’s an evolution of how the team has built on and innovated the process.

While Kubo was in development, the only color 3D printer on the market was 3D Systems’ Z650, a powder/gyp-sum-based printer Laika used on ParaNorman and Boxtrolls. It could be used for the human characters in Kubo, says Director of Rapid Prototyping Brian McLean, but not for Monkey, Beetle, and the Moon Beast.

“We would have to find a new technology to achieve the director’s vision, or force a redesign of those characters to soften those hard edges,” he says.

For McLean and Technical Director Rob Ducey, the latter was not an option.

Alternatively, Stratasys – whose plastic, non-color polyjet printers had been used to cast Coraline’s hand-painted faces – was beta-testing the Connex3, the first color multi-material resin printer. Alas, it could only print three of five colors: white, black, cyan, magenta, and yellow.

“So right off the bat, we were running up against serious limitations in the way color was assigned,” says McLean.

Furthermore, Stratasys’ bundled printer software limited how those three colors could be mixed – a problem for Laika, which had grown accustom to painting detailed, gradated textures that could be jetted down onto a powder substrate. Still, the new plastic polyjet technology was so proficient at printing – with unfailing repeat-ability the fine feature details of Monkey’s face and fur, the Moon Beast’s lamellar body, and the sharp nose and hard facets of Beetle’s armor-like head – that the benefits far outweighed the drawbacks. The RP team’s only challenge was color matching the conceptual art.

To that end, Laika bypassed the bundled software and had expert 3D printing engineer Jon Hiller develop custom slicing software that would allow for gradient shading and fine color details. Hiller’s new driver could output a giant 3D bitmap that told the printer where to place each microscopic droplet of cyan, magenta, yellow, black, white, or clear resin in the exact proportions to replicate the color of the digital model. Hiller also improved Stratasys’ color model by equating and indexing specific ratios of 3D resins with their real-world measured color.

“The final hurdle was convincing Travis [Knight] that the faces of Monkey and Beetle could be simplified to three colors,” says McLean.

Initially, there was some fear that the subsurface scattering of the Z650 powder-based humans might seem incongruous next to that of the resin-based creatures, by the way light reflected, refracted, and raked across their faces (the Z650 printer jetted down color a sixteenth of an inch into the powder substrate).

The fear proved unfounded, however, when they discovered the UV-cured resin of the polyjet technology was inherently translucent. The subsurface scattering of Monkey and Beetle has a similar quality to Kubo, even though they’re made out of plastic.

MAKING FACES

The Connex3 produced thou-sands of high-resolution color sculpts for Monkey and Beetle, providing over 13 million possible facial expressions for Beetle and 30 million for Monkey. In total, 15,581 faces were made for monkey on the Connex3, while 23,197 were printed for Kubo on the Z650.

No matter the printer used, the head-modeling process always began with scanning a clay maquette into Autodesk’s Maya. Then, modelers refine the topology in both Maya and Pixologic’s ZBrush before sending it to the printer. After incorporating subtle artistic changes from Knight, the modeler simplifies the geometry in PixelMachine’s Topogun and decides where to split the mouth and brow, while riggers outfit the face with simplified facial controls for shaping the expressions.

Working in Maya, the CG modeler then collaborates with the fabrication lead to engineer the internal components for the head. “This means [Laika’s modelers] have all the problems of modeling for a CG production, along with a myriad of concerns stemming from creating a physical object: minimum material thicknesses, printer resolution, mechanical tolerances, and so forth,” says Lead 3D Modeler Ty Johnson. “The majority of a modeler’s time is spent breaking the head into over 70-plus mechanical parts that have to fit into the head the size of a golf ball.”

Because 3D printing files have always been polygonal, Laika’s RP department has found Maya perfectly suited for handling both the soft- and hard-modeled geometry, and ensuring they function together.

Next, a small group of digital animators fashion the vast digital library of expressions used throughout the film. Then, animators are assigned shots in the film, for which they pull shapes from the pre-existing library or create special expressions and send a Maya Playblast of the facial performance to the editorial department. If approved by the director, the CG animator compiles the list of faces for the shot, requesting pre-printed expressions be pulled from the physical face library and sending the special expressions off to the 3D printer. Once printed, the faces are cleaned, sanded, and tested before delivery to the stage on the day of the shoot. Because Knight was demanding such a finely pitched acting style, tending to these “special expressions” became an almost unending occurrence.

“On Coraline, our job was creating different phoneme shapes to string together for lip syncing,” says McLean, “but over the course of the last few films, it [became more] about very subtle acting and getting as much emotional range from these little puppets as possible. We’d provide Travis with Playblasts, and he’d kick them back with acting notes asking, for example, for a slight tilt in the brow. Our pipeline wasn’t designed for this level of scrutiny. It was designed for building a library of hundreds of faces in advance that could be delivered to the set and reused over and over. So sometimes we didn’t have the correct expressions in the predetermined kits, which forced us to go back into Maya, and animate and print faces especially for the shot.”

In keeping with this push for greater emotional range, a face was no longer animated every other frame, like on ParaNorman, and instead changed expressions 24 frames per second. Moreover, the animators shaped the main characters’ performances from a reference bible that borrowed from some of the finest acting touchstones of our time.

THE MOON BEAST

While the RP department was able to deliver textured puppets for Kubo, Beetle, Monkey, and almost every other character in the film, bringing the Moon Beast to life required more than advanced voxel printing. The Connex3 forged 130 parts for the snake-like fish, including the intricate lamellar scales, the armor-like plating, piranha-like teeth, and spinous dorsal fin. But achieving its eerie, turquoise luminescence demand-ed an intricate dance between RP, visual effects, compositing, and the skills of Director of Photography Frank Passingham.

Emerging at the climax, the Moon Beast slithers across dark, swollen skies like some serpentine poltergeist, descending fangs-bared upon Kubo as he flees through the village. Though Visual Effects Supervisor Steve Emerson and Composting Supervisor Peter Vickery could have created the effect digitally, the potential for inconsistencies between the miniature sets and puppets, let alone betraying the Herculean effort involved in rapid-prototyping the entire character, demanded a solution that was more faithful to the film’s practical roots.

“We ended up realizing there was no reason we had to photograph this puppet under one lighting scenario,” McLean reveals. “We could shoot the puppet under multiple lighting scenarios and give those passes to the VFX department, which could then pull masks and composite various looks together.”

Although the Moon Beast’s concept art features shades of jade and turquoise, along with sequins of topaz, the team ignored the color, and instead print-ed the primary puppet as one model in a three-color palette of white, black, and clear resins of varying densities, gradients, and transparencies.

Then, adding a gold Mylar undercoating on the clear sections, UV paint on other areas, and photographing the puppet under three lighting passes – key, fill, and UV – they were able to pull various mattes from the result-ing array of contrasts, tweaking the colors and compositing them in The Foundry’s Nuke. Under the white light key and fill passes, the black would almost disappear, the white would pop, and the gray sections (constituting a blend of white and black) would yield a milky tone.

“The UV pass was like a matte pass out of CG, so we’d get really selective mattes; that was key to getting the luminescence,” says Vickery. “We would get all these fine stroke lines along the edges of the fins, for example, that popped out in UV. Then, we were able to shift the color [in Nuke] and create a matte to make those areas glow, while still keeping the whole body from turning into a big, glowing mess. We also used the UV paint for the eyes, which had to represent the moon.”

To cast the threatening shad-ow the creature trails through the village, the VFX department extracted mattes from the shad-ow passes, in addition to the white light and UV passes, before compositing the layers in Nuke to achieve a consistent look across all 65 of the Moon Beast’s shots.

Martin McEachern

OCT. 21, 2017: LAIKA at Portland Art Museum | Opening Conversation

My friend and follow cinephile K.Grant informed me of this event that began yesterday at the Portland Art Museum. Wish I was there to attend, but thanks to media team at LAIKA you and I have front row seating to this in depth look into the team of crafters who make every film so magical. Below is the press release and footage of the opening conversations with panel moderator Rose Bond (far right), featuring LAIKAns (left to right) Ollie Jones (Director of Practical Effects), Deborah Cook (Head of Costumes), Brian McLean (Director of Rapid Prototype), Georgina Hayns (Puppet Fabrication Supervisor) and Brad Schiff (Animation Supervisor).

I wish they had invited Chris Peterson (Cinematography), Nelson Lowry (Production Design), and Steve Switaj (Head of Camera and Stage Engineering) but I’ll search for video to address these seen and hidden elements which makes Laika such an innovative animation studio.

portland Art museum press release

This fall, the Portland Art Museum and the Northwest Film Center celebrate Animating Life: The Art, Science, and Wonder of LAIKA, a groundbreaking view behind-the-curtain into the visionary artistry and technology of the globally renowned animation studio.

At the heart of every LAIKA film are the artists who meticulously craft every element. Through behind-the-scenes photography, video clips and physical artwork from its films, visitors will be immersed in LAIKA’s creative process, exploring the production design, sets, props, puppets, costumes, and world-building that have become the studio’s hallmarks. Their films are a triumph of imagination, ingenuity and craftsmanship and have redefined the limits of modern animation.

“Portland Art Museum and Northwest Film Center are thrilled to partner with LAIKA to present the wonders of this distinct enterprise,” said Brian Ferriso, The Marilyn H. and Dr. Robert B. Pamplin Jr. Director and Chief Curator of the Portland Art Museum. “LAIKA at its core is an artistic endeavor that embraces the past and infuses it with a 21st-century vision. LAIKA’s aesthetic vocabulary continues to be shaped by the people and uniqueness of this special state.”

Established in Portland, Oregon in 2005, LAIKA has produced four Oscar®-nominated features, including Kubo and the Two Strings (2016), The Boxtrolls (2014), ParaNorman (2012) and Coraline (2009). Among LAIKA’s many accolades is a 2016 Scientific and Technology Oscar® for its rapid prototyping system, which uses 3D printers to revolutionize film production. Through technological and creative innovations, LAIKA is devoted to telling new and original stories in unprecedented ways.

“We believe storytelling is an important part of who we are,” says Travis Knight, President & CEO of LAIKA and the director of its most recent award-winning film, Kubo and the Two Strings. “LAIKA embraces our great privilege to tell stories by creating films that bring people together, kindle imaginations and inspire people to dream. We are proud to be able to showcase our creative process through this partnership with the Portland Art Museum, one of the country’s greatest art institutions, and the Northwest Film Center. Art in its finest forms speaks to our shared humanity, opening us up to new ways of thinking and feeling and helping us to recognize the hidden connectivity of all things. With this exhibit, LAIKA, PAM, and the Northwest Film Center have created something that can be part of that communal process of change and connection.”

During the course of the exhibition the Northwest Film Center will present wide-ranging programming showcasing the studio’s work and surveying the evolution of stop-motion animation since before the turn of the 20th century. Along with film exhibition programming, the Center will offer a range of animation classes, workshops, and visiting artist programs for students, artists, families, and community members of all ages, including exhibition offerings in its Global Classroom screening program for high school students.

In a city renowned for its maker scene, Animating Life: The Art, Science, and Wonder of LAIKA and its related film and educational programming will be a celebration of the intersection of art, craft, film and technology. Proudly embracing the studio’s unconventional, independent Portland spirit, the exhibition and programs will serve to celebrate LAIKA’s singular position in Portland and in the global film community.

Organized by the Portland Art Museum and the Northwest Film Center in collaboration with LAIKA.

APR. 26, 2017: Graduating is Next Month = 45.5149° N, 122.9392° W

With classes winding down and I begin this next chapter in my profession within the animation industry, I’m really hoping that my senior thesis group project allow myself and my team to move forward with the goals. For me it has been a goal to work at LAIKA in the character design department, mainly in the rapid prototype department. I’ve put in the applications and now I must rely on the portfolio to tell what I can bring to the team. I was packing up and came across this great piece from OPB on the studio. Enjoy and I’m hoping the next post I share highlights my transition into my real at LAIKA…

FEB. 19, 2017: VFX Supervisor Steve Emerson

Making expansive worlds with enormous effects and several characters has always been a daunting task for stop-motion filmmakers. The reason is simple – if it’s in the film it has to be built. From puppets to buildings to salt shakers and the salt within, an artist needs to create tangible, real-world objects in order for them to be captured in-camera with real-world lighting. Coraline, LAIKA’s first feature film, was captured almost entirely in-camera. But as the scope of LAIKA’s films grew, the studio embraced technology to create unique, stylized universes unlike anything seen before in the stop-motion genre. LAIKA’s hybrid approach evolved during production of the studio’s subsequent films: ParaNorman, The Boxtrolls, and their current feature, Kubo and the Two Strings.

In this presentation, VFX Supervisor Steve Emerson guides attendees through the history of visual effects at LAIKA (in-camera and digital) and the evolution of the studio’s production processes over the past 10 years. He examines LAIKA's live-action approach to visual effects, the specifics of their workflow, the technology they’ve embraced, and what the future holds.